Subterranean Extremophiles

From the extreme heat of hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean to the seemingly inhospitable realm half a mile below the ice of Antarctica, life has been found thriving on Earth in environments that were once thought too extreme for survival. These hearty organisms, called extremophiles, not only show how life on Earth can adapt to just about any environment imaginable, they also suggest that life may be possible in similar harsh conditions beyond Earth. In 2021, a team of researchers from the University of Rhode Island's Graduate School of Oceanography discovered just how these microbes are able to survive in the seafloor sediment.

Seemingly cut off from the usual sources of food and energy like sunlight, which enables photosynthesis, the subseafloor microbes are sustained by the radiolysis of water molecules. Naturally occurring elements in sediment and rock, like uranium and thorium, emit radiation which can split water molecules into hydrogen gas and oxidants. It is the hydrogen gas produced by this process which was found to be the main source of energy for these extremophile microbes. Moreover, the amount of hydrogen produced by this process was found to be amplified by the very sediment in which the microbes were living. Compared with samples of seawater and distilled water, a sample of wet seafloor sediment was found to produce nearly 30 times more hydrogen compared with the water-only samples.

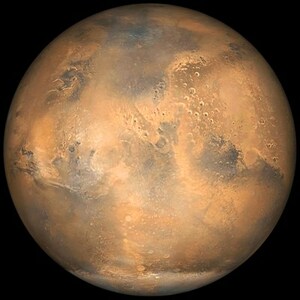

This finding is particularly timely as the search for life using rovers to collect and analyze the rocks and soil on Mars continues. The discovery of this new type of subsurface microbe on Earth suggests another possible avenue for life to have existed on Mars, if not in the present, possibly in the past, when Mars had a wetter climate.